What’s in a name?

On Labeling and Identity

Friend—is it ok if I call you friend, even if we might not know each other in real life? The thing is, I want you to know that I care about your feelings. As such, I’m worried that some part of this musing might upset you, which is—in no way—my intent. But I think it’s the nature of the beast when it comes to labels, and it’s a beast I feel compelled to discuss. Know that if you don’t feel like being upset today, I will not be the least bit offended if you choose not to read on. I trust you to make the best decisions for you.

If you’re still here, what I’d invite you to do is to think about which part(s) you find upsetting, and why. And if you feel compelled to do so (respectfully), please share. I believe that there are learning opportunities for all of us in these feelings, which is why I’m bringing my ideas forward. Like most of the topics that move me to write a WTF Just Happened? post, this one doesn’t have a clear “right” or “wrong” answer, nor does it have an easy solution. Come to think of it, none of the truly interesting ideas do, do they?

OK, here goes nothing.

I’ve just come back from an almost indescribable retreat in which I spent several hours with one of the most powerful “understanders” of our time, Emelie Cajsdotter. In her session on empathic interbeing, Emelie stated that the web of life functions best when each individual being has the freedom to become totally, unapologetically, themselves. (I’d encourage you to spend some time with that idea and then think about how it makes you feel differently about giving the side eye to someone on the bus whose wardrobe choice doesn’t vibe with your own, or telling your dog not to bark at coyotes, or even pulling a weed for that matter…).

As a person who has spent much of my life studying and celebrating differences, this idea resonates with me deeply. As such, I spent some time at the retreat practicing learning to see the individual people, places, and things around me as they are. For example, in one exercise, we introduced ourselves to one another using only our hands, and I came to understand things about both my friends and relative strangers that I wouldn’t have known otherwise. It was with this renewed sense of connection through appreciation of uniqueness that I returned home to my flock, my pack, my herd, my community, and my home.

On the drive back from the airport, one of my favorite minds (which belongs to my husband, Andrea) regaled me with stories of what’s been going on in the world “out there” while I was gone. Though there have been many turns of events (Kimmel fired? then hired back!) the thing that grabbed my attention was that the research of our friend Kristina Olson had become the center of a political controversy. There are different reasons why I didn’t like hearing this, and they are not limited to the fact that Kristina is my friend. She’s also an incredibly careful scientist whose research has cleverly investigated sensitive topics that we don’t really understand—like how children develop constructs of race, social status, and gender.

In Andrea’s initial telling of the story (which I’ve since looked up to refine so bear with me), the Economist wrote an article titled How stable are the gender identities of younger children? in which it took a particular slant on the conclusions of a recent report that Kristina and colleagues wrote looking at how gender identity does and doesn’t change over time. According to Andrea’s report, the article—which claims that one in five children who switch gender change their minds—failed to consider the fact that the switch was mostly not back to their natal sex, but to “another” category of transgender (and this is the point at which car gossip amongst scientists separates a bit from facts so please bear with me). “Wait, there is more than one different type of transgender?” I asked with genuine curiosity, trying my best to keep up with the times. “Yes,” Andrea said, displaying the confidence of his father, Luciano.

The truth, as I understand it now after looking at both the monograph and the article that came out, is that most of this “switching” of gender identity is into the “gender diverse” (or non-binary) category. Now, I am not an expert in gender constructs, but my understanding is that non-binary is a term used for people with a different set of experiences that can either feel like a mix of both genders, like no gender at all, or like their gender moves fluidly between male and female. These seem like different experiences to me, and I wonder—will this shared desire not to be labeled with either the male or female traditional gender identities ultimately be replaced by three new labels?

Remember when we were either gay or straight? How many of the identities represented in the LGBTQIA2S+ acronym are you aware of?

And this brings me to the musing of interest, which I swear will eventually relate to brains…

I think the challenge here, when it comes to identity and belonging, is that labeling is (and always will be, I think) a double-edged sword. The truth, at least as Emelie Cajsdotter and I see it, is that each of us is truly unique. Those of us who study differences for a living are interested in defining and understanding the ways we vary. And though we argue about how many different axes of variability there are,[1] and how to measure them, I think we all agree that the number of ways people vary is finite.

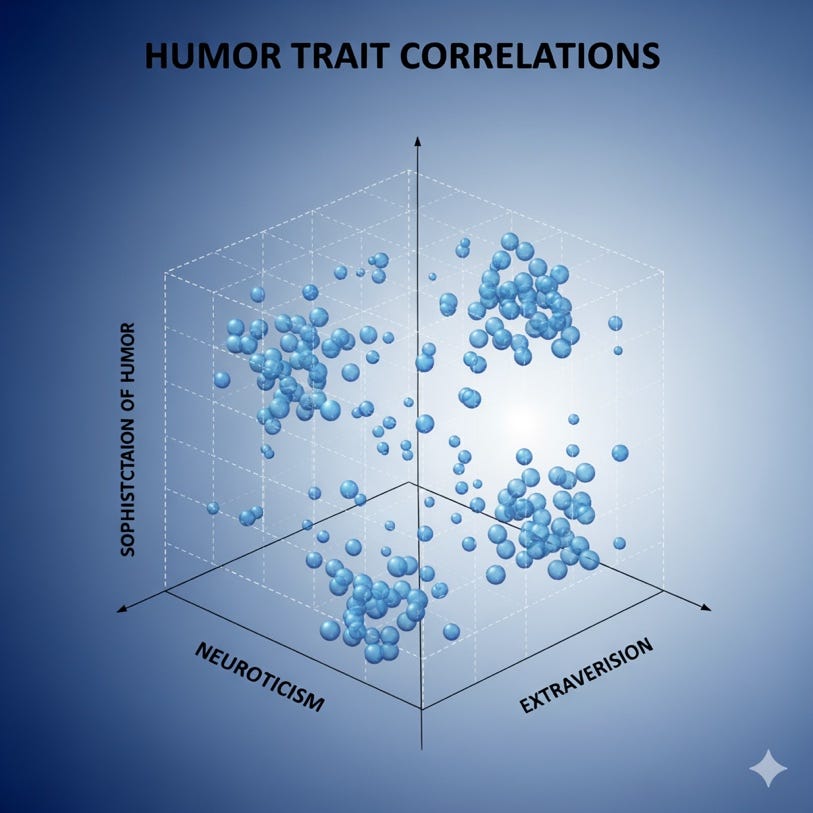

Let’s imagine, entirely for the sake of argument (and also because it’s within the limits of my ability to imagine things spatially), that the number of axes over which people vary is only three.[2] I’ve labeled them “extraversion” and “neuroticism” (which are probably real things) and “sophistication of humor” (which is definitely a real thing). Now note that most, if not all, of the interesting ways that people vary are not binary but are continuous variables (or spectra). I’ve asked Google’s AI Gemini to draw this space for me and to plot a bunch of pretend people in random combinations on the axes below.

There are a few things to notice here. The first is that even with only three variables, there are ample ways for people to be different. None of these 100 or so pretend people bubbles is occupying exactly the same space. Imagine how that scales up to 4000 characteristics, or whatever number of variables is necessary for defining precisely who you are when you have the freedom to become totally, unapologetically yourself.

The second thing to note is that we see what looks like “clusters” of people forming in this space. In the real world, when we’re defining and measuring these different variables, we often notice that certain characteristics tend to “move” together in populations of people. In the world Gemini and I co-created, for instance, there are a group of highly extraverted and moderately neurotic folks who also have a very low-brow sense of humor (aka the Jesters) and another group on the opposite side of the spectra of introverts with low neuroticism and a highly-sophisticated sense of humor (aka the Wednesdays).[3] In the real world, we might see things like distractibility and hyperactivity moving together, or narcissism and antisocial behavior. And when we do, it’s quite tempting to give that “type” of person a name, isn’t it?

But what’s in a name?

The first time I remember thinking about this idea in any depth was in graduate school. I was taking a clinical psychology course, and we were asked to debate the use of diagnostic labels. The more I thought about it, the more opposed I was. Though I now understand that I’m more of a “splitter” than a “lumper” by nature (perhaps this is yet another important dimension of variability between people), what struck me at the time was how different individuals within the same diagnostic category could be. For instance, some people diagnosed with schizophrenia are catatonic—presenting with immobility or incredibly reduced affect and mannerisms, while others—like this man I did not know (in the biblical sense or otherwise) who once insisted that he was the father of my child—have delusions of grandeur or paranoid hallucinations. My argument at the time was that if the goal was to treat the client who was showing up to be helped as their unique self, proving a label like schizophrenia might be more harmful than helpful.

The question then becomes, how many different axes do we need to explore to understand how to help, and how long does it take to measure them?

Though the argument I presented in graduate school is old, to the best of my knowledge there are clinical psychologists today who also believe we should be treating symptoms and not syndromes. In an article written for the association for Behavioral Analysis International in 2024, Jennifer McComas hits many of the points we discussed more than 20 years ago. The Pros of mental healthcare “labeling” she lists include:

· Access to healthcare and services provided with certain diagnoses

· Improved treatment planning

· Facilitated communication between care teams

The Cons include:

· Implying etiology—labels are often associated with biological destinies

· Creating stigma

· Oversimplifying the human experience

My interest in this topic has been renewed with the recent uptick in diagnoses of neurodivergence in adulthood. I’ve watched, with fascination, as people I know and love (the most recent of which being my husband) get identified with some time of neuroatypicality—like ADHD—as adults. Though both of us understood on some level that Andrea (and probably me too) would meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD, I wasn’t prepared for his emotional response to the diagnosis. “I’ve never felt so seen,” he said upon his return from the psychiatrist.

And since his POV is consistent with others I’ve known and trusted in this situation, I’d like to add a bullet point to the PROs, with some caveats to come:

· Belonging

Though my deepest experience with labeling comes from the field of neurodivergence—or various clusters of ways of being that are related to brain function and generally believed to be either atypical or dysfunctional—I think the Pro of belonging and the Con of oversimplification can be more broadly applied to the labeling process.

Let’s try it on for size.

I’m going to generate a list of adjectives that correspond to a bunch of different axes of being. I’d like you to put the words “I am” in front of them and just explore how you feel about it. Note, this is not a vocabulary test, so if I’ve chosen a word and you’re not quite what it means, feel free to look it up!

Ready?

I am ________

female

young

black

neurotypical

distractable

extraverted

healthy

stoic

intelligent

bisexual

anxious

contemplative

sensitive

tall

athletic

unpredictable

generous

One thing I’d like to note is that some of these axes are probably more relevant to your specific sense of self than others are. This may have to do with perceived societal value, or the extent to which you’re different than “average” on that scale, or any number of other things related to your ability to be totally, unapologetically yourself.

I once served on the committee of a student in the Foster Business School who was studying various threats to identity. The work she did for her Ph.D. seemed to suggest that we’re more sensitive to threats to some of our labels than to others, and that this sensitivity was related to how tightly our identity was tied to those labels.

Now, imagine learning that neuroscientists have discovered a particular pattern of brain design and lived experiences that shape the way each of those 16 axes rise and fall together which ties all of the different axes together. Then I tell you that your particular pattern of warmness and coolness over these characteristics is called “toucan.” That would be kind of cool, wouldn’t it?

You never realized that people with X characteristic (e.g., very tall) also tended to be more Y (e.g., unpredictable) on average. But as you start proudly identifying yourself as a toucan and meeting others like you, you might notice that most of them seem more sensitive and contemplative than you feel on average. Perhaps there’s an impulsive toucan subtype that has yet to be identified? Maybe toucans who are over 50 show up differently than those under 50? Does it matter if you have children?

I hope you can appreciate that the toucan exercise is not meant to make light of existing labels, whether they be clinical diagnoses or social constructs. My only goal is to let you feel through the different kinds of match between labels of ways being and what you know to be true about you. Because I think the most obvious beginning to this double-edged sword of our relationship with labels should start by getting to know ourselves in relationship to them.

I also wonder what happens to people when the scientific understanding of these labels, or cultural awareness of them, changes. For instance, how did people diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome feel when that stopped being a thing that was distinct from, but related to autism, and became part of the autism spectrum? Or what about people diagnosed with ADD (no hyperactivity), who now learn that it’s no longer a “labeled distinction”?

The truth, as I see it, is that every label is necessarily a shortcut. The labels we hold most tightly can both define the “us” and oversimplify the “me.” And since belonging is such an essential human need, the pressure to identify with a label may be high. However, when you ascribe to a label, are you also reducing your own dimensionality or dynamism? What if you added a modifier to the adjectives? I am ____ when…

I am stoic when other people are depending on me.

I am extraverted when I am well rested and surrounded by people I trust.

I am friendly when others are open to receive my kindness and interest in them.

Now let’s turn this label thing around to how we understand others. Note the way that some of the labels (e.g., race, gender, height) are observable from the outside, while others involve varying degrees of inference. How might the labels we ascribe to others interfere with our ability to know them exactly as they are? How might we create spaces for others to be totally, unapologetically themselves?

As I promised in the beginning, I don’t have answers, nor do I have admonitions. I’m only inviting you into this place of figuring out how we might come to understand one another better, and what role labels play in the process.

[1] Fun fact, though the Big Five personality test is among the most widely accepted (OCEAN) assessment of behavioral differences, Gordon Allport (one of the fathers of personality testing) listed over 4000 traits in his catalogue of individual characteristics.

[2] It isn’t.

[3] I used all of my creativity making up those labels. Please feel free to name the other two groups and drop them in the comments!

Definitely lots to ponder here. I have thought about labels quite a lot over the the past few months and can totally see the benefits of ‘a diagnosis’ or belonging, it had also worried that it would confine someone into a ‘box’. I’m sure it’s something that will keep evolving in my mind.

PS. I prefer ‘best friend’ but friend will do 😂

I enjoyed your take.

And it made me think of a talk I went to recently by the author of The Einstein of Sex. I hadn't heard about Magnus Hirschfeld before, but it sounds like he was one of the first to academically express ideas around the multitude of dimensions that come into a person's gender/sexual identities. If you also hadn't encountered him, I think you would enjoy this book.